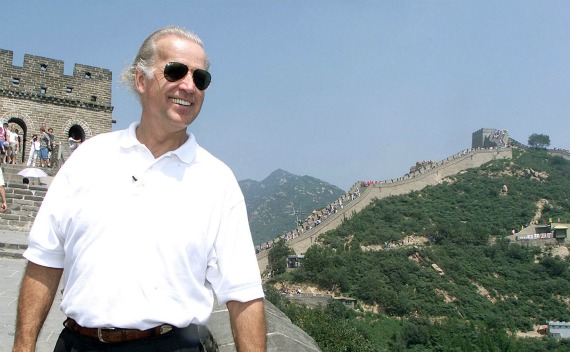

What Will Vice President Biden Find in China?

More on:

Next week Vice President Biden heads to China for a round of talks with the country’s current and future leaders. Certainly it is not the easiest time for the vice president to make such a trip. Few things have been as dispiriting as the terrible heat waves the United States has endured this summer, except perhaps the state of American politics. Our president seems lost, the Democrats marginalized and voiceless, and the Republicans an ugly house divided.

So, in the midst of this U.S. political and economic funk, what is the reception likely to be in Beijing? What is on the mind of Chinese observers and media analysts? Are they similarly bearish on the United States? Were all the predictions of a serious loss in U.S. international prestige on target?

Here is what I found:

If Vice President Biden needs a feel-good moment, he might drop by for a chat with the Dean of International Studies at Peking University, Dr. Wang Jisi. His interview in the Global Times suggests that at least some Chinese think the United States still has some something to share with the world. In the interview, “US Power Strong for Decades” (the title is perhaps a bit over the top) Dr. Wang says, “Four reasons have contributed to the overwhelming power of the U.S. The tradition of rule of law ensures the nation’s political stability. The consistency and continuity of its social values guarantee the nation’s internal cohesion, enhancing its unique sense of patriotism. Technological and systematic innovations provide great power for society to move forward. And, a highly developed civil society generates strong self-correcting ability which prevents the nation from being led astray and committing strategic errors when dealing with external affairs.” (I think that this message may have been as much about what China has yet to do as about what the U.S. is good at.)

Predictably, there is a lot of talk about China’s holdings of U.S. debt. People’s Daily writer Ding Gang, who previously was based in the United States—and generally is a poster child for why spending time in the United States does not always lead to better feelings about America—sees an opportunity at this moment for China to use its Treasury holdings to pressure the United States on the issue of arms sales to Taiwan. He calls members of the U.S. Congress “arrogant and disrespectful” in ignoring China’s core interests by pressing President Obama to sell F-16 C/D fighter jets to Taiwan. Ding proposes a range of possible retaliatory moves such as stopping U.S. Treasury bond purchases, requiring international credit rating agencies to “demote U.S. Treasuries,” and launching trade sanctions against the states where members of Congress support Taiwan arms sales. Ding might look at the U.S. experience in trying to use its so-called “economic leverage” to influence China to get a sense for how likely such linkage is to work.

Striking a smart balance, I think, is Shen Dingli, director of the Center for American Studies at Fudan University. He raises a central issue for Vice President Biden, “Given the U.S.’s increasing difficulty in balancing its federal budget, how might it cope with the rise of Asian maritime powers, including China?” Shen’s response is useful: “Retaining America’s leadership in Asia depends on the [sic] U.S. innovation—spending less, saving more and reducing the debt. Other countries could help by importing and spending more, as their trade surplus with the U.S. contributed to U.S. borrowing. A prosperous Asia Pacific has to be built through collaborative effort.”

All of these views from some of China’s most prominent U.S. watchers suggest that Vice President Biden is unlikely to hear anything in China that he hasn’t heard before—either from the Chinese or from advisers and analysts here in the United States. The challenge, of course, is what he is going to do about it. As Shen suggests, the buck stops here.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store